On the topic of realism in worldbuilding.

Worldbuilding is one of those things people start doing unadvertedly since they’re little. It is of human nature to imagine other worlds, stories and characters and make them pursue heroic feats. Many children engage in worldbuilding without knowing it has a name and a dedicated community: this is so common, that I would consider storytelling and worldbuilding basic instincts. The same way you start to draw or write from a young age, you play with your imagination.

Everyone wishes they were a child again. The lack of responsibilities! The lack of care for the thoughts of others! Many of us desire that carelessness. We do what we want to do, and it doesn’t matter if it’s good or bad. We had fun in the process, and that’s why we did it in the first place. Many artists look back at their first pieces and cringe at them, but also envy the innocent mind with which they made them. As we grow up and mature, perfectionism takes a hold of us and makes us want to do the best work ever, a work that will be accepted by a publisher so that everyone will read it, or even make us earn money. That, I believe, is the victory of the capitalist society over us. It firmly grasps our true desires and replaces them with the need to earn a living and turn our hobbies into businesses.

It is most likely that, in this situation, you gradually lose your interest on a craft that gave you countless hours of enjoyment. Instead of having fun with it, you burn yourself over the necessity of it being perfect and thus successful. If it won’t make you money, then it’s useless: not because your aim was to make money in the first place, but because you’ve been told that your highest aim must be to monetize your interests in order for it to not be a waste of time. Unproductive time is wasted time.

Besides the obvious influence of capitalist society over us, there are many other instances of us losing interest on our hobbies because of external forces. When we’re not a child anymore and we start lurking on the internet, it’s not long until we discover communities of those with similar interests to us! If we’re a worldbuilder at heart, we’ll be keen to talk with those interested in worldbuilding too. This, at least, is what happened to me: I felt extremely happy because I didn’t know it was such a widespread practice, and I had access to the wisdom of people who were better than me.

I learned the jargon, I studied the different ways to start and improve my worldbuilding, and I was also subjected to the criticism of others in an indirect manner: I was and still am an introvert (even on the internet), so I didn’t feel like showing my own work back then. Instead, I read the criticism others received, and thus I started learning what was “right” and “wrong”.

If you’ve ever been in Worldbuilding circles, most likely you’ll have read some of these at least once:

Rivers don’t split.

Tolkien races such as elves or dwarves are boring, don’t use them.

Your climates and biomes are wrong. Here, read this college-level geography book so you can fix them.

Those mountains are unnatural because there is an endhorreic basin there and they’re very unusual so you must fix it right know even if you don’t even know what that is.

You have x cliches in your world, no one will like your work if you keep using them.

Obviously I’m exaggerating a little bit for humorous purposes, but you see the deal: I do things this way, you must too. I don’t like this, so you can’t do it. Things don’t work this way in real life, so you must fix them in your world.

I see two main schools of thought in the worldbuilding communities: The realists, whose main interest is to create worlds as akin to real life as possible, and the traditionalists, who tend to create worlds that fall into the usual fantastic setting of “I did things this way because I liked it.” The realists develop complex systems of plate tectonics to create their mountains and landmasses, while the traditionalists draw their continents and mountain ranges however they like it, as long as it seems good enough to them. The realists read about currents, atmospheric cells and physics to develop their climates, and the traditionalists place their biomes wherever they want, as long as it has a minimum logic. Realists seem to be studying their world, while traditionalists treat their worlds like a painting: you painted this because you wanted it to be there.

Let me make this clear: I respect and defend both of these paradigms. My intention is not to declare one as better or worse than the other. However, there’s a problem with imposing your worldbuilding methods on others without knowing what their interests are. I can’t even begin to count the times I’ve read posts of aspiring worldbuilders grieving because they had been told that their world wasn’t “realistic enough” and that they weren’t able to “fix” their world because they couldn’t bring themselves to read about real-life processes and apply them to their work. This happens a lot. It’s sad, everyone. It’s so sad. People are not having fun with worldbuilding because they’ve been told that their world must be perfect, the same way capitalism disheartens us to keep pursuing our interests because our works aren’t marketable. We’re losing potential worldbuilders because we expect them to do things the same way we do without knowing their motives.

There was a time when I almost stopped doing worldbuilding because I tried to keep my world as realistic as possible, and because that wasn’t my true goal, it sucked the fun out of it. I thought that no one would be interested in my world because they would find mistakes, nitpicky mistakes, that would turn everything into an useless mess. Only when I started doing what I wanted did I start enjoying it again.

If worldbuilding starts feeling like a chore to you because you keep trying to make it as realistic as possible, then you must stop and rethink your choices. Worldbuilding, mapmaking, it’s all supposed to be fun as heck. A world doesn’t need to be realistic to be interesting. Does it matter that a river splits? Does it matter that a certain mountain range isn’t likable enough to professional geographers?

And before you tell me anything: Does it really matter?

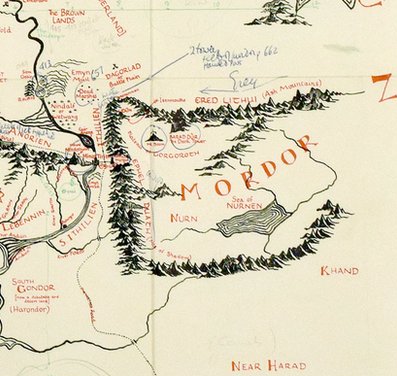

The Middle Earth isn’t the most realistic continent ever: there are a lot of jokes on the mountains that surround Mordor because of their unrealistic shape.

That doesn’t stop people from considering LOTR one of, if not the best, fantasy stories of all time. You’re still interested in the Middle Earth because it has a huge and complex history, full of compelling characters and civilizations, each with their own logical cultures and myths. That’s what makes a world credible.

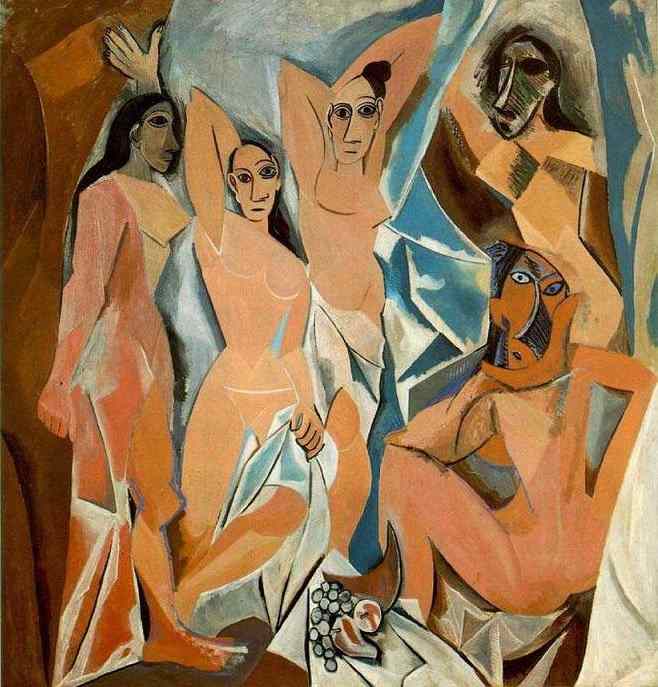

These two paintings are both by Picasso:

Cubist painters like Picasso didn’t just draw random shapes on a canvas. They developed their own styles based on the abstraction of their previous knowledge.

What if we strive for a middle ground? You may want your world to have an overall credible geography, but you don’t want to spend months torturing yourself over it. Maybe you want to give your personal touch to it. What I suggest is to educate yourself on those matters, like how real climates work or how the continents of the Earth came to be, but then to use that knowledge you gathered to do what your heart tells you. You have the theory, but you choose what to do in practise. This works with everything else, from cultures to economy, any topic you can talk about in worldbuilding. When you have a basic knowledge to work with, you can trust yourself to give your world an internal consistency.

If you want to create the most realistic world ever, try it! If you just want to make a world however you like, do it! If you like a cliche, use it! With moderation, that is. If you want to do something just because it looks cool, make a good explanation for it and go ahead! Do whatever your heart desires! The only things your potential readers will care about the most is internal consistency, variety and your personal touch. Try to follow those tenets, and you’ll have fun while making an interesting world others will like.

Every person is different. I have some preferences, you have others. Have fun and look for criticism that will actually help you grow as a writer. What we must never lose is our endless pursuit of knowledge.